Reserved Occupations and Exemptions

The Haslam Family and Reserved Occupation

Bernie, Elsie’s brother, as far as can be found did not go to war despite being of 34 years of age. Due to the loss of official records over the years there is little written evidence and as a result much is unknown as to why he did not. One initial explanation was Bernie, as a farmer, may have been held back from War to manage the land.

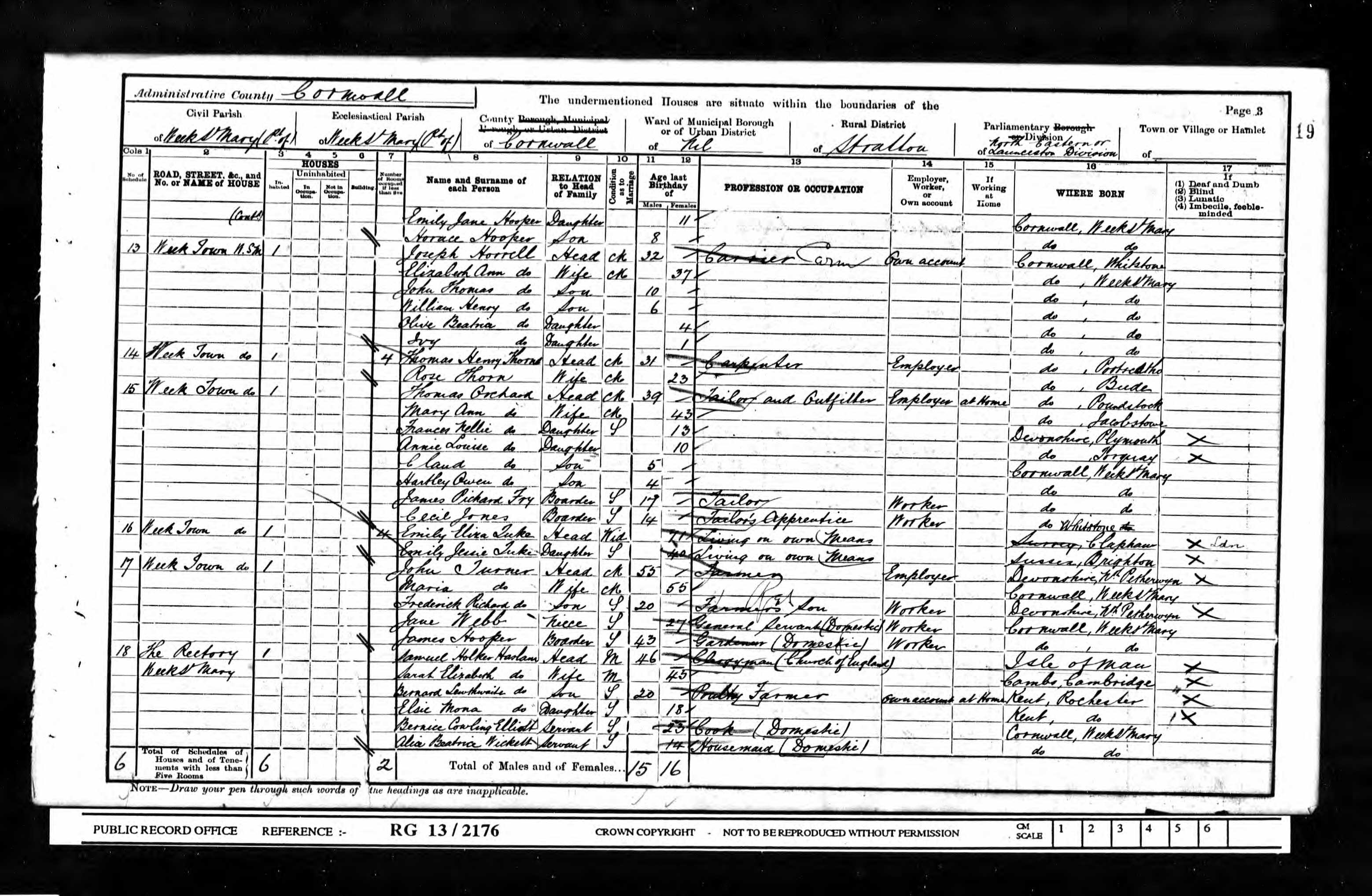

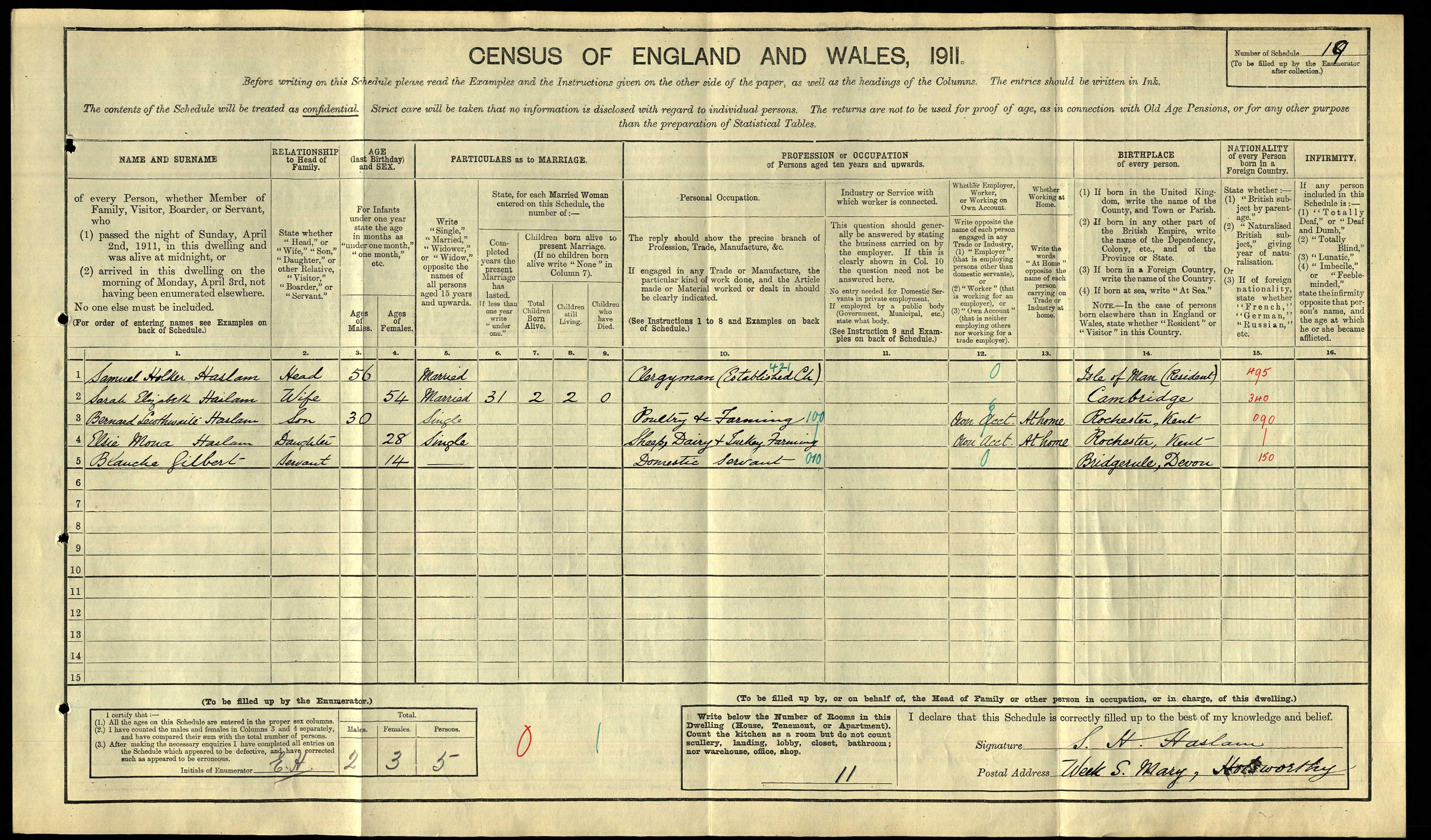

In both the 1901 and 1911 census’ Bernie is listed as working as a poultry farmer in Week St. Mary, ‘own account’ meaning he worked his own farmland wherein he neither employed or was employed by any other persons.

In her diary entries attached below, Elsie writes that Bernie did have to ‘register’ and attend an ‘audit meeting[s] in Stratton’. This continues to happen incrementally over the course of the war. The date that Bernie starts attending the audits aligns with the initial push for recruits began: September 1914.

25th September 1914

Transcription: ‘… Father + I took Bernie + Thomas [a local farm hand] to an audit meeting at Stratton called at Stamford Hill to take a Register to old Mrs Kingdom + then home in time for tea’.

© From the collection of the RIC.

© From the collection of the RIC.

3rd March 1915

Transcription: ‘Father took Bernie + Horrell to the audit at Stratton in the aft[ernoon]. Charlie went with them + on to Bude to see the recruiting sergeant about enlisting.’

© From the collection of the RIC.

© From the collection of the RIC.

16th June 1915

Transcription: ‘Bernie + Father + Knight (from edd Mill) went off to am audit at Stratton at 11:45am + got home at 1.30pm. I had a lot of letters to write in the afternoon. We packed up a parcel for Mrs Gabbins + sent it to a German prisoner [of war] camp, to a Pte [short-hand for the military service rank ‘Private’] in the Middlesex Regt [short-hand for Regiment].’

© From the collection of the RIC.

© From the collection of the RIC.

In 1918, however Elsie writes of Bernie that he had a medical ‘re-examination’ and that he has ‘passed G3 again’. Leading us to believe that by at least 1918 Bernie was medically exempt from being conscribed or enlisting for G3 regulations state that those persons: whose limitations resulting from a known medical condition do not pose an unacceptable risk to the health and/or safety of the individual or fellow workers in the operational/work environment;

[or] who may require and take prescription medications, the unexpected discontinuance of which will not create an unacceptable risk to the member’s health and/or safety would be unfit for duty.

6th May 1918

‘…Bernie got his “call-up ‘for re-examination’‘.

© From the collection of the RIC.

© From the collection of the RIC.

Continued from 8th May 1918 entry.

‘… Bernie passed G3 again!!’ © From the collection of the RIC.

© From the collection of the RIC.