The Derby Scheme

“… Men could either enlist voluntarily or ‘attest’ [which meant they would] be obligated to enlist as soon as they were required.” Fiona Reid, Medicine in The First World War Europe: Soldiers, Medics and Pacifists (London: Bloomsbury Academics, 2017), p.182.

With the idea of a war that would be ‘over before Christmas’ proving to be complete fallacy, one last attempt was introduced in order to avoid conscription, this was known as ‘the Derby Scheme’.

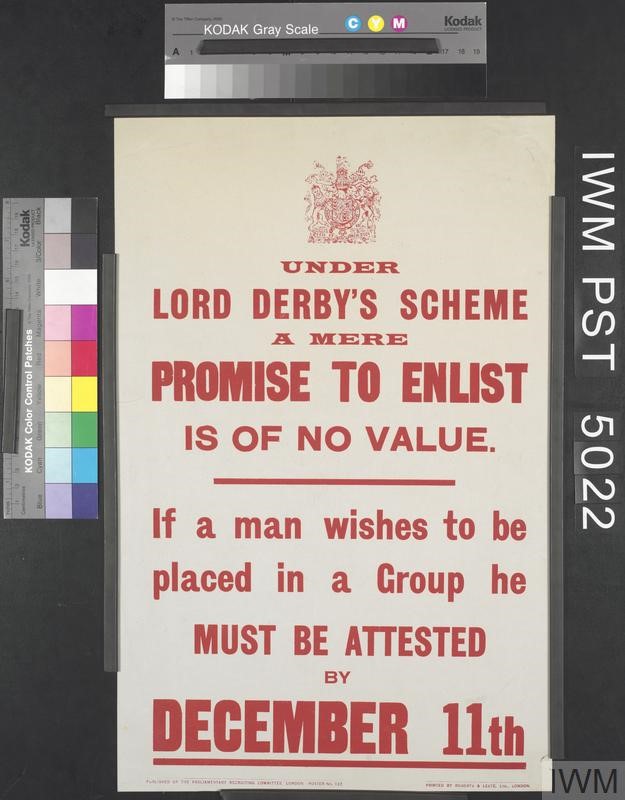

© IWM (Art.IWM PST 5022) By late 1915 the numbers of those enlisting could not keep pace with mounting casualties, but the Government wanted as many men as possible to join the forces willingly, so they introduced the ‘Derby Scheme’.

Named after its inaugurator, Edward Stanley – 17th Earl of Derby and Kitchener’s new Director General of Recruiting, the Derby Scheme was described by many as ‘a kind of moral conscription’. A way to drum up volunteers while still having reluctant men believe there might be a chance they could get away without fighting.

Running from October 1915 to December 1915, the Derby Scheme urged men aged between 18 and 41 who were NOT in a ‘starred’/ reserved occupation to attest. Men who attested did so on the understanding that all ‘single men’ would be called up before the youngest married or ‘widowed-with-children’ counterparts. (Volunteers married on the day of, or after registering though would still be deemed as ‘single’ and would be called upon first.)

© IWM (INS 7764) An armband, to be worn with their civilian clothes, was issued to all men who had formally attested for Army service. This was done so it could be easily recognised who had attested and who had not. Those who had attest but were declared ‘medically unfit for service’ were also given an armband; this was important for due to the rising societal pressure for men to be seen to be ‘doing their duty’ those remaining at home needed to adequately validate the reasons for doing so.

By the scheme’s closing date 38 per cent of single men and 54 per cent of married men had still failed to enlist – many publicly refusing to do so. This ultimately forced the British Government to institute compulsory military service in 1916.

The difference between ‘enlisting’ and ‘attesting’:

To enlist was to join the military and serve without delay, while to attest was an official ‘promise’ of sorts obligating the man in question to fight if he was required to. Attesting men were assigned to a unit and given a military record but they did not officially serve until their whole unit was called up to do so.